A New England Journal of Medicine CPC provides a wonderful illustration of why clinicians will retain their central role in diagnosis despite the advent of computer assistance in diagnosis.

A 72-year-old woman complained of dysarthria, dysphagia and pharyngitis that had developed over preceding days. She had severe obesity and a 3 year history of exertional dyspnea and had sought care in the previous year for transient facial asymmetry and slurring of words.

Physical exam was notable for “subtle ptosis in the right eye”, right facial droop and pitting edema in both legs.

The clinician addressing the case, Dr. Stephanie V. Sherman, made the key observation that:

In a complex case, it can be helpful to identify the features in the background, middle ground, and foreground that form the overall clinical landscape.

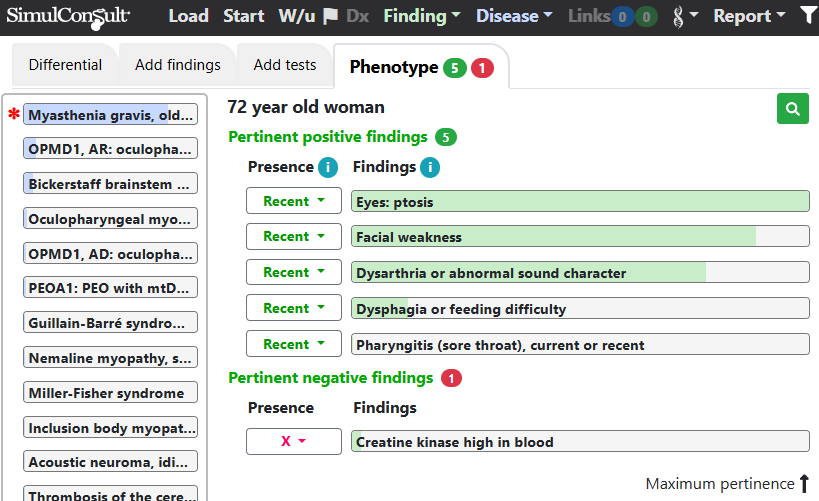

Following this approach, we chose the following findings for running the case through the SimulConsult diagnostic decision support (subscribers can load these findings by clicking here):

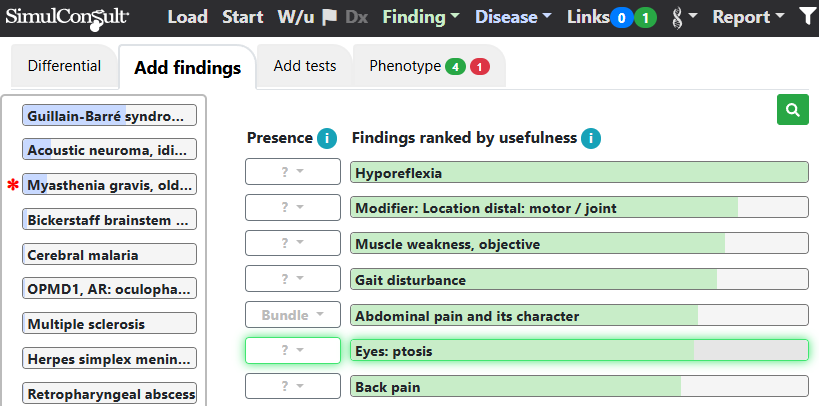

As in Dr. Sherman’s assessment, myasthenia gravis was the leading diagnosis before any further testing. As can be seen in the figure, the clinical observation of ptosis which was noted to be “subtle” was scored in the software as having the highest pertinence (green bar). However, had ptosis not been noticed, the software would have been helpful as shown in the figure below (note that because of ptosis no longer being included, the green badge in the findings tab now counts only 4 positive findings). In this scenario, ptosis would have been one of the top findings shown in the display of useful findings in the “Add findings” tab, prompting the clinician to check for ptosis.

Although dyspnea is a finding noted in myasthenia, we didn’t include it in the patient profile because it seemed to be a “background” feature with onset 3 years previously in an obese patient with pitting edema. In myasthenia, dyspnea is typically an acute symptom, constituting a “myasthenic crisis”.

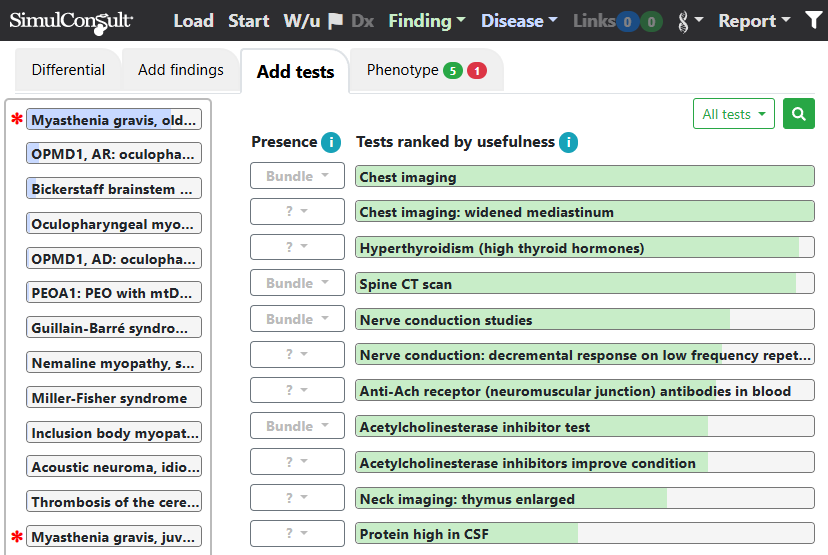

The differential diagnosis in the SimulConsult software includes some disease not considered in the NEJM article, such as Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis. Useful tests suggested in the “Add tests” tab (figure below) suggest assessments such as checking CSF protein, which was found to be normal in this patient, which would reduce the probability of brainstem encephalitis if entered as a pertinent negative.

The overarching message of this case is that it is crucial for the clinician to decide which findings are in the “foreground”. Relying on software to make this determination based on textual analysis of the entire case would be error prone. However, software such as SimulConsult that keeps the clinician “in the loop” and prompts for useful findings can be very helpful: it focuses the clinician on additional findings to check while mulling the differential diagnosis.