When diagnosing a patient, it is important to consider the totality of the patient’s findings and understand their influence on the differential diagnosis. The most relevant findings present are referred to as “pertinent positives” and those absent as “pertinent negatives”. To do this it is important to understand what is meant by pertinence. It is a retrospective metric of the influence on the differential diagnosis of knowledge of findings already known to be present or absent. In the software pertinence is determined using a computational statistical analysis of the findings and the differential diagnosis.

Pertinence is important in several situations:

- Sometimes the differential diagnosis depends heavily on one pertinent finding, and it is crucial to know whether that finding has been determined reliably.

- Sometimes one lab test has low pertinence to the differential diagnosis. This is sometimes the case for tests ordered without sufficient prior thinking about the patient.

- Sometimes using a combination of pertinent findings is the best way to diagnose a patient and communicate the reasoning to colleagues.

Example to work through

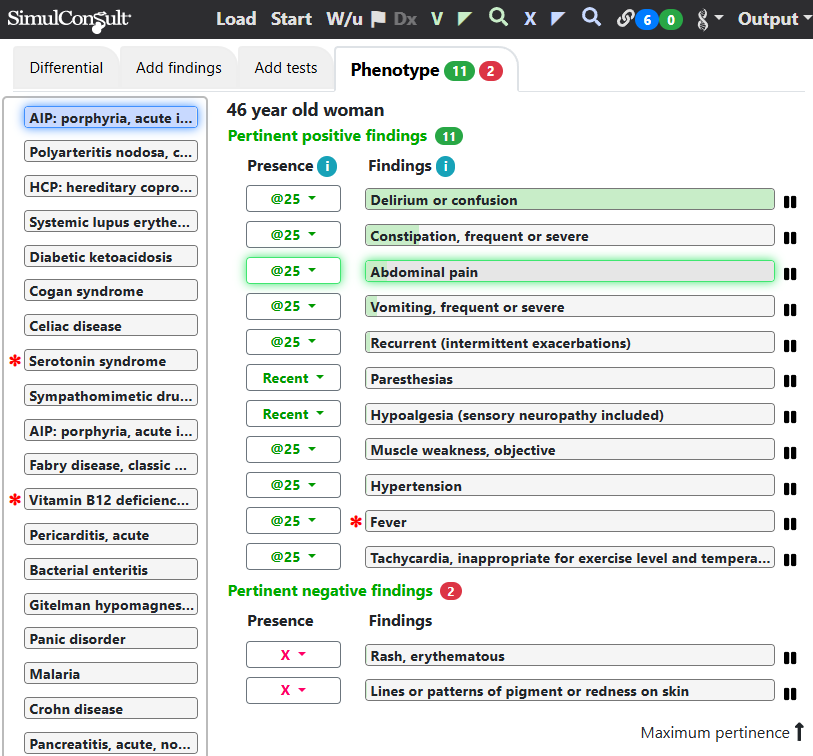

A good example comes from a case in the 1 November 2009 New York Times Magazine Diagnosis column “Perplexing Pain” by Lisa Sanders MD. It describes a 46-year-old woman with a 23 year history of “attacks of abdominal pain and fever that lasted sometimes for weeks … None of her doctors had been able to figure out what was causing the strange episodes of devastating illness” that led to 13 surgeries, including resections of her appendix, both ovaries and much of her colon. She also reported paresthesias (an abnormal sensation of tingling, prickling, burning, or numbness in the skin). She said that “It’s really been a nightmare … it just seemed as if every time [her internist would] come up with some theory about what was going on and treat that, another symptom would pop up. It was like the arcade game her children played, whack-a-mole — you get rid of one problem, but then it would pop back up, along with another and another.”

The doctors were focusing on one symptom at a time, and indeed many of these findings had significant pertinence (green shading on findings in the figure). The key to diagnosis was considering a combination of several pertinent findings. (Registered users can click the image below to jump into the software; some videos may be helpful in navigating from there)

The error was focusing on one finding at a time, and not considering their combination, which was suggestive of porphyria. The cognitive error associated with excessive focus on one finding instead of considering the totality of information is called “Anchoring”.

This page is part of a series on the Elements of Diagnosis.

Copyright © 2025 SimulConsult