A 14 February 2018 article “Her Various Symptoms Seemed Unrelated. Then One Doctor Put It All Together” in the New York Times “Diagnosis” feature by Lisa Sanders MD describes a difficult case. Doctors were unable to come up with a diagnosis for years until one heroic doctor figured out the answer.

It started years earlier, the older woman told her. Almost every night, she would get these crazy fevers. First came bone-rattling, shaking chills; she couldn’t get warm even under a pile of quilts. Then suddenly she would be roasting hot, with sweat pouring off her. Her temperature would spike to 102 or 103. And her whole body would hurt, right down to her bones. She popped Tylenol constantly just to keep her fever down.

Then an hour after the fever hit, she would start to feel sick and throw up until she had nothing left in her. This happened almost every night.

During the day, she felt weak and tired, and her bones hurt. It made any movement painful. Her doctors called it fibromyalgia. She also had a rash. Hives, the doctors told her. It didn’t itch, but no one could figure out why she had it. And, her daughters added, she had no appetite. The very thought of food made her want to vomit, the older woman told May. She’d lost over 80 pounds this past year.

Dr. Jori May, an internist in her second year of training, ordered some lab tests and and enlisted several specialists to help:

May waited anxiously as the results came back. It wasn’t H.I.V. It wasn’t syphilis or celiac disease. The patient didn’t have multiple myeloma either, though that test, which measures levels of one part of the immune system known as antibodies, was abnormal; one antibody, known as IgM, was high. May referred the patient to an infectious-disease specialist, who found no infection. The oncologist found no cancer. And the dermatologist merely confirmed what May already knew — the patient had hives, and it wasn’t clear why. She presented her puzzling patient to every smart doctor she knew when she walked down the hospital hallway and at educational conferences. Yet after seven months of testing and referring and discussing, May was no closer to a diagnosis than she was on Day 1.

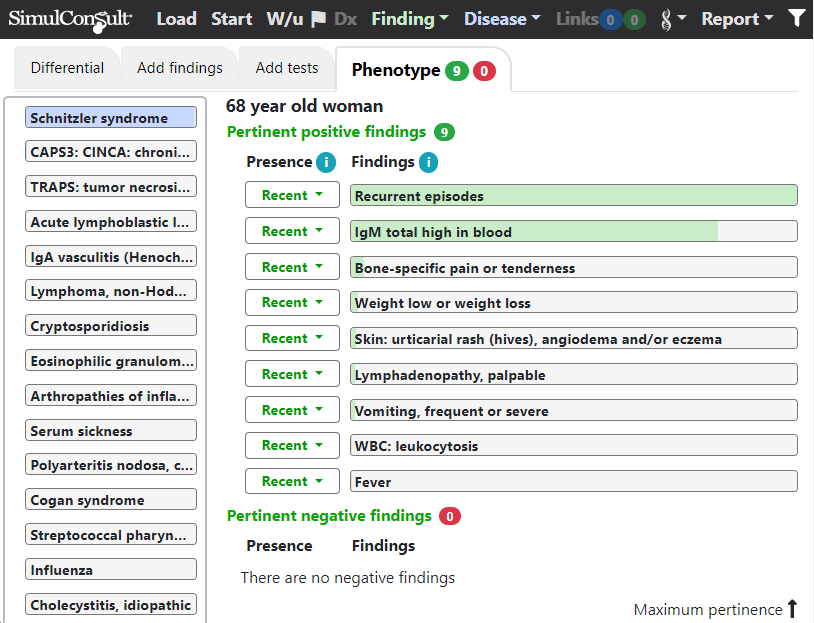

All of these findings are relatively non-specific, and adding them into the SimulConsult diagnostic decision support software shows that there is no “pathognomonic” finding in this case – many of the findings have high pertinence (green shading). However, their combination is strongly suggestive of Schnitzler syndrome:

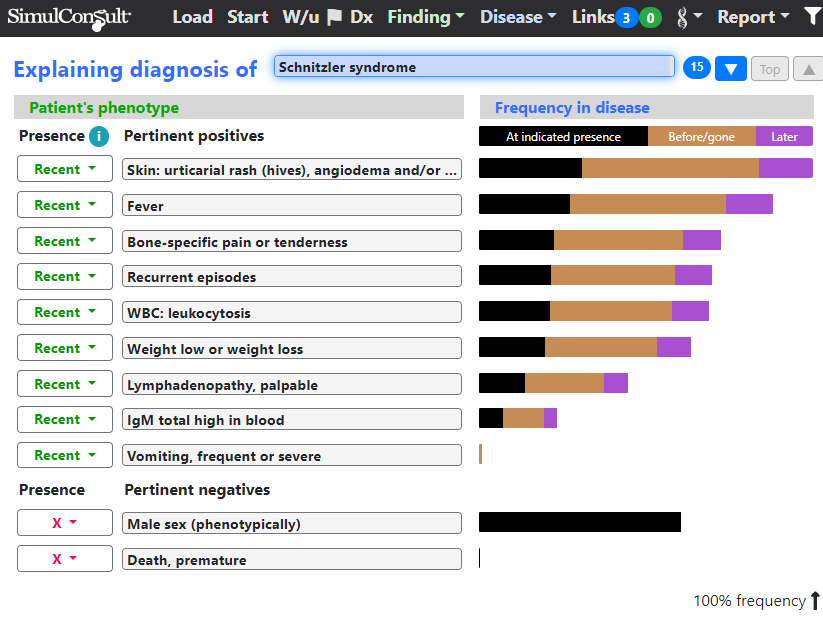

The “Explain Diagnosis” screen shows the match between the findings and the diagnosis:

It was a heroic pathologist going who went beyond the call of duty and put together the clinical picture:

One afternoon she was surprised to see an 11-page note from a pathology resident who, as far as she knew, was not involved in the case. It was a meticulous summary of all the patient’s symptoms as well as the many tests performed so far. He went on to suggest that she had a disease May had never heard of — Schnitzler syndrome. It was, as the resident described it, a rare and poorly understood immune disorder.

However, as illustrated by this case, diagnostic software available to any clinician can reduce the need for heroism and shorten a “diagnostic odyssey” from years to minutes.

SimulConsult subscribers to the software can click the following URL to load this case:

There are more clinical cases here.