A concrete guide to the theory of diagnosis

Classically, diagnosis has been learned by watching others, but doing only observation is not optimal:

- Many skills are needed for diagnosis.

- Learning implicitly by observing experienced clinicians and intuiting what they are doing is hit-or-miss.

- Not all clinical teachers are good at explaining what they do, even if they are great diagnosticians. Many are not even aware of the processes they use. Even among those who are aware, few have the time to explain their thinking.

Here we provide a description of the key skills involved in diagnosis, the “Elements of Diagnosis”. Each element has the text of a case describing the Element. Registered users of the SimulConsult diagnostic decision support software can click the images to get into the software with the patient’s findings and the relevant screen and settings, making it possible to keep going with the case. The software has a database of >9,600 diseases, so even medical students can practice the Elements long before they know the details about many diseases. Learning these Elements will make it easier for trainees at all levels to get more out of their implicit learning from watching seasoned clinicians.

All users of the software have the ability to generate links to open the software on the Dx screen with their own set of patient findings. To also specify the relevant screen and settings a menu option is available by request.

Key terms to know

Students early in medical training need to become familiar with the following terms:

- Findings include patient-reported symptoms, clinician-observed signs, family and exposure history, and test results (including both lab and radiology results).

- Diseases have a set of findings associated with them. The Disease Phenotype refers to this set of findings in a disease. Individual findings are sometimes called phenotypic features. If the cause of a disease is poorly understood its collection of findings is sometimes referred to as a syndrome.

- Patient phenotype is the collection of findings in the patient, including both pertinent positive and negative findings.

- A diagnosis is a disease that a patient is considered to have. The word diagnosis is also used to refer to the process of reaching a diagnosis.

- A differential diagnosis is a list of diseases that a patient may have, ranked by their likelihood (like a bar chart). Typically, only one of the diseases in the differential diagnosis is the actual diagnosis.

- The process of differential diagnosis is the iterative process of collecting information, re-evaluating the list of likely diseases, and then deciding what information would be most useful to collect next.

In real life, the distinction between a finding and a disease is less crisp. Some findings have the same name as diseases. For example, there are a number of diseases called Diabetes, but there are also hundreds of genetic syndromes with diabetes as one of its many findings. Electronic health records deal with this lack of crispness by merging findings and diseases together into a “Problem List”, instead of keeping separate lists of “Diagnoses” and “Findings”. Sometimes several “isolated” findings are later recognized as part of a single diagnosis.

Reasoning from findings to diseases

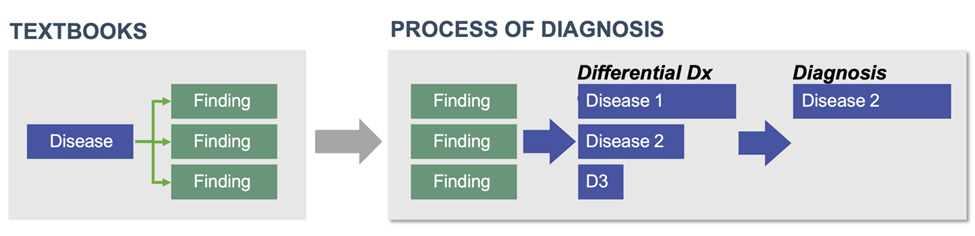

Medical textbooks are typically organized as descriptions of diseases. They organize information by saying that patients with a particular disease will have a recognized set of findings. In the process of diagnosis, however, a patient arrives with a set of findings, and it is your job to put them together into the patient’s diagnosis. This requires you to invert your knowledge, to go from findings to diseases instead of what is learned in textbooks, going from diseases to findings.

Keeping multiple options under consideration

The Differential Diagnosis has a clinician keeping multiple options (diagnoses) open and under consideration. Others consider doing so to be exceedingly difficult, but clinicians learn to do this on a daily basis.

| “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” F. Scott Fitzgerald |

Getting oriented

Throughout this material, color has meaning. Findings are green and diseases are blue. Since many of the names of diseases and findings may be unfamiliar to you, and sometimes findings and diseases share a name, knowing the color codes will help you stay oriented to what is being shown.

In almost all of the images in pages about the Elements, registered users of the software can load the diagnostic decision support software with the same patient information by clicking on the image to follow along with the example.

The information in the diagnostic decision support database is continually updated to reflect new knowledge, so the images in the educational materials may differ from what you see in the diagnostic software.

Throughout this material about the Elements of Diagnosis, you can think of the diagnostic software as a sandbox – a place to explore diagnostic thinking. It is also useful for trainees to reconstruct the thinking of the attending physician on rounds. Finally, trainees as well as attending physicians find the tool helpful in clinic.

There are short videos about how to use the software here.

In images in the pages about the Elements you will see the top black Navigation bar of the diagnostic software. When using the software, you can hover over these navigation options to see a tooltip explaining what each does.

21 concrete Elements of Diagnosis (and cognitive errors they reduce)

Each of these elements is linked to a page describing the element:

| Element | Error avoided (Cognitive) | |

|---|---|---|

| Start | Disease probability depends on the care setting | Availability |

| Cognitive mode: Free-form combinations of findings | Framing | |

| Cognitive mode: Workups | ||

| Cognitive mode: Suspected disease | Premature closure | |

| Emergence speed | Neglecting speed info | |

| Transmission (Family, exposure) history | No transmission clues | |

| Iterative | Finding: Foreground and background | |

| Finding: Usefulness | Zebra retreat | |

| Finding: Negative findings and finding frequency | Confirmation bias | |

| Finding: Pertinence retrospectively | Anchoring | |

| Finding: Age of onset and disappearance | Neglecting onset info | |

| Finding: Caution | Garbage in | |

| Finding: Rarity | ||

| Disease: Rule in/out | Representativeness | |

| Disease: Treatability | Morbidity & mortality | |

| Testing | Cost | Wasting money |

| Delays | Elapsed time to diagnosis | |

| Bundles (tests inform about many findings) | Undervaluing tests | |

| Clinical correlation after testing | Underappreciating tests | |

| Closure | Explainability | Clinician out of loop |

| Risk with diseases | Treatment malpractice |

What you should avoid: 7 cognitive errors

Doing diagnosis in one’s head involves many shortcuts. These have the advantage of speed, but can have the disadvantage of cognitive errors that result in misdiagnosis. Many of these shortcuts can be understood as omitting one the 21 elements of diagnosis. One of the advantages of using diagnostic software is that it reduces the pressure to cut short one’s thinking because it reduces the work needed to assemble large amounts of information. Although cognitive errors occur in only a few percent of cases in medical practice, those can result in costly diagnostic odysseys and errors that can delay treatment or result in erroneous treatment.

7 cognitive errors

- Framing: after others suggested a diagnosis, not exploring findings that don’t fit

- Premature closure: jumping to a diagnosis and failing to consider alternative diseases

- Availability: probability of diseases assigned by vividness of memory

- Zebra retreat: not exploring the possibility of a disease because of its unfamiliarity

- Representativeness: dismissing a disease that doesn’t match the classic clinical pattern

- Confirmation bias: failure to consider pertinent negatives

- Anchoring: focusing excessively on one finding

Copyright © 2025 SimulConsult